Welcome to Three Things.

This is our main monthly issue of three items to help you engage with God, neighbor, and culture.

Are You a Tree, or a Potted Plant?

Joy Clarkson on Psalm 1 and our longing for roots

Joy Clarkson's family moved sixteen times as she grew up, six times internationally. When she left home for college and graduate studies, the pattern continued with a yearly move seven years in a row. Longing for rootedness, she eventually began to liken herself to a potted plant:

Perhaps after all these years of life with portable roots, I was no longer capable of natural rootedness. Perhaps if you tried to plant me in a particular place, I would shrivel up and die, not ready for the exposure of pure obligation to a place. I longed for a place to belong, to be entangled with, but felt in my bones incapable of such a thing.

Around this time, she encountered Augustine's Confessions and his metaphor of the Christian life as a pilgrimage toward a homeland. The metaphors began to mix: “I am a potted plant; I am a pilgrim.” This, she soon discovered, is the mixed metaphor at the heart of the first psalm:

The blessed person walks, like a pilgrim (v. 1), but the blessed person is also like a tree (v. 3). At first the psalm begins as a simile, but it unfolds the likeness in metaphor; the righteous are not only like the tree, they are planted, yielding, prospering. At the heart of these two images is not only the (not) nature of metaphor but also some of the central tensions of what it is to be a human. We flourish in rootedness and fruitfulness, but that rootedness is always temporary, interrupted by death. And even in life we are driven by longings this world never seems capable of satisfying. By reflecting on the properties of trees and journeys, and carrying them over to the human condition, we might discover new ways of understanding ourselves.

Read Are You A Tree? over at Plough. It’s an excerpt from Joy’s recent book, You Are a Tree: And Other Metaphors to Nourish Life, Thought, and Prayer.

A Better Political Compass

Evan Riggs on our four new political camps

The USA is set for a rematch. (FYI, you don’t need to choose.) As a tumultuous political season unfolds, Evan Riggs is convinced that we need a better political compass to reduce the chances of friendly fire.

The old compass, inherited from previous decades, had an X-Axis for the political Left and the Right where the key difference was one of economics. The Y-Axis, on the other hand, was social, with authoritarian arrangements at the top and libertarian freedom at the bottom.

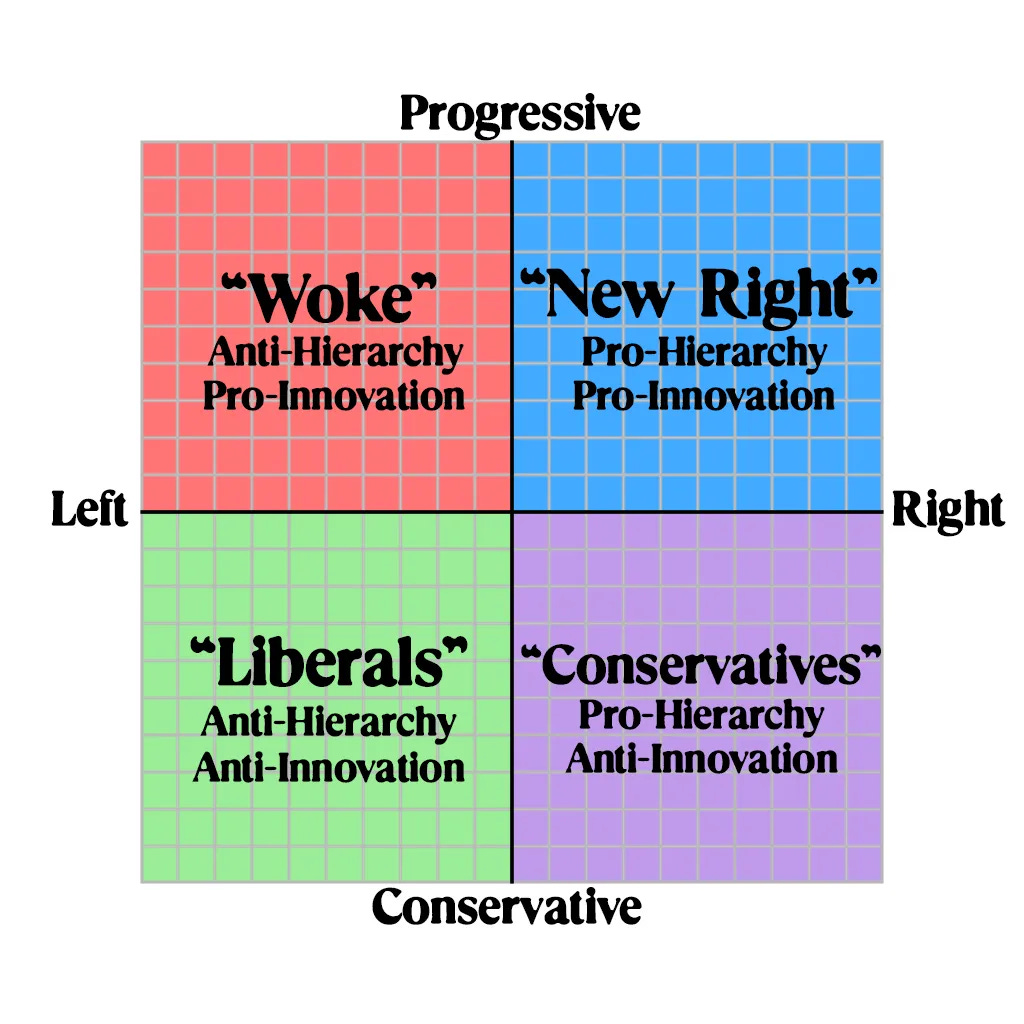

Bring this compass into our current political debates and you’ll only be confused, writes Riggs. The new compass looks like this:

The Left-Right X-Axis is no longer about economics and the Y-Axis is no longer about social arrangements. On the new compass, writes Riggs,

The X-Axis is a Moral Scale based on different moral foundations. The easiest way to understand it is by acceptance of hierarchy, with the far left striving for total equity while the far right strives for a perfect caste. The Y-Axis is an Innovation Scale, with Progressives generating new ideas for the future while Conservatives try to preserve the past. Anyone below the X-Axis supports liberalism, anyone above it does not.

Roughly generalized, this is what the four camps look like:

Right-Wing Conservative: “Right-Wing Conservatives are conservatives as you know and love/despise them, the ones who can’t help but go one about how things just ain’t like they used to be.”

Left-Wing Conservative: “These are your standard issue liberals. If you consider yourself “politically homeless,” a “centrist,” have ever thought, “I didn’t leave the left, the left left me,” … you also probably belong here.”

Left-Wing Progressive: “These are the Woke. They are also often called “leftists” or "progressives” by our left-wing conservatives (aka Liberals) to differentiate themselves from them.”

Right-Wing Progressive: “This is the “New Right,” the hardest-to-define quadrant of the four, due to its relatively new prominence.”

The political battles of recent years have been between (2) and (3). We’re ramping up for some tussling between (3) and (4).

Read A Better Political Compass over at The Burn.

Mammon or Marriage?

Bradford Wilcox on what’s missing from our “Midas mindset”

The mythical King Midas once wished that everything he touched would turn to gold. Most modern people are in a similar position. Everywhere we look, says University of Virginia sociologist Bradford Wilcox, a "Midas mindset" is caught and taught. We are inclined to believe that the only things worth touching are those that yield affluence: education, career, personal brand management. Wilcox writes,

The message is clear: leaning into work, rather than family life, is the path to prosperity. But this seductive message in our individualistic age is completely at odds with the facts.

Those facts provide the foundation for Wilcox’s recent book, Get Married: Why Americans Must Defy the Elites, Forge Strong Families, and Save Civilization. The title cheekily points out a glaring inconsistency at work in modern discussions of marriage. As Wilcox puts it in an excerpt from the book at The Atlantic,

many elites today—professors, journalists, educators, and other culture shapers—publicly discount or deny the importance of marriage, the two-parent family, and the value of doing all that you can to “stay together for the sake of the children,” even as they privately value every one of these things. On family matters, they “talk left” but “walk right”—an unusual form of hypocrisy that, however well intended, contributes to American inequality, increases misery, and borders on the immoral.

In public and in private, for the sake of our own flourishing and that of our communities, we would do well to exchange the Midas mindset for a marriage mindset. Successful marriages in the modern world are buttressed by five pillars. Wilcox unpacks them with data in the talk above, but here’s a preview:

Communion — a sense of “we before me” in a marriage

Children — recognizing that children depend upon the stability of their parents’ marriage

Commitment — ensuring fidelity and loyalty

Cash — being intentional about money (statistically, no separate bank accounts)

Community — being surrounded by people who support the marriage

Watch (or listen to) the talk, check out the book, or read some excerpts at The Atlantic (The Awfulness of Elite Hypocrisy on Marriage) or The Free Press (Why You Should Get Married).